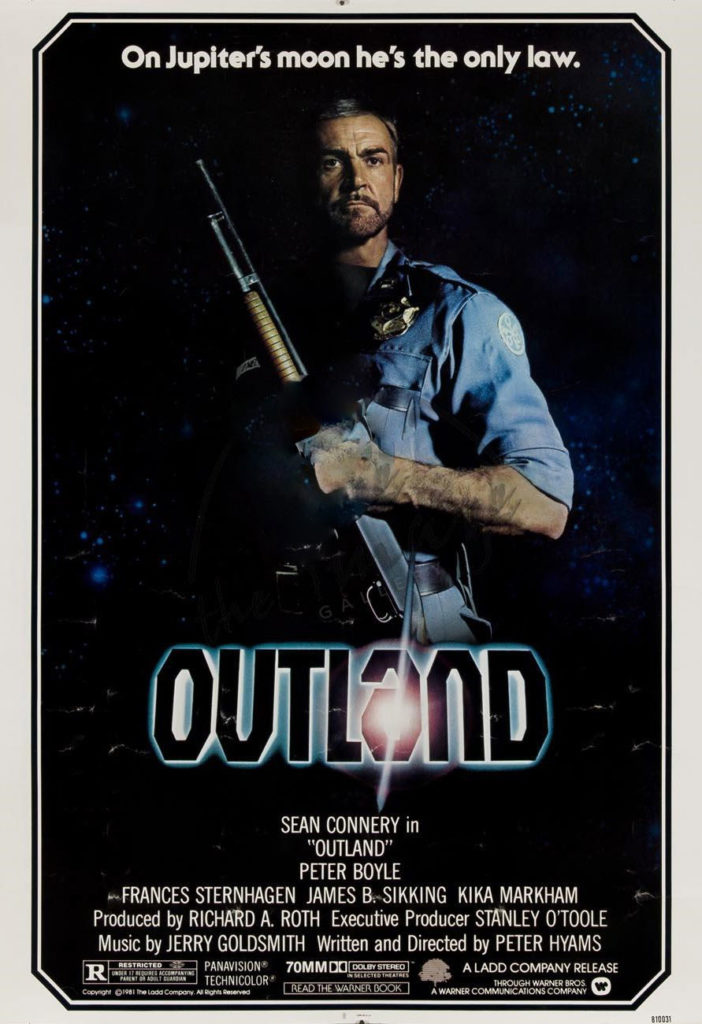

Outland, the 1981 film written and directed by Peter Hyams, is two movies in one. Most of it is a crime story, heavy on the grit and with a fair amount of menace (helped along by Jerry Goldsmith’s grim score). Then in the final act audiences are given a western, evocative of the film High Noon. And all of it is wrapped in a sci-fi setting.

It’s the future, and off-planet mining is big business. The Jovian moon of Io is the site of a massive titanium mine, where workers are shipped in for year long tours to work in the harsh environment and, presumably, take home some decent pay for their troubles.

Sean Connery plays William O’Neil (as it is spelled on his uniform — in his emails and in the end credits it is spelled as O’Niel, but I’m going with the spelling that is least annoying to me), a federal marshal who has only started his tour two weeks earlier. O’Neil is a bit of a hard-ass, bringing proper police work to a mining station that has seen law enforcement go kind of lax.

That’s because the station is run by the slimy Sheppard (Peter Boyle). Since he arrived to take control of the station, production has gone through the roof. He attributes the success to working his miners hard, and in return, letting them play hard. Sheppard is happy, the workers are happy, the company, most importantly, is  happy — everyone is happy. Except for the miners who kill themselves in the most gruesome fashion — by exposing themselves to Io’s thin and deadly atmosphere. They are not happy. But these poor miners aren’t killing themselves because they’re depressed or suffering from some malady brought on by the hardships of working out in space. Rather, they have been taking designer amphetamines to increase their ability to work, and after a number of months, the drug fries their brains.

happy — everyone is happy. Except for the miners who kill themselves in the most gruesome fashion — by exposing themselves to Io’s thin and deadly atmosphere. They are not happy. But these poor miners aren’t killing themselves because they’re depressed or suffering from some malady brought on by the hardships of working out in space. Rather, they have been taking designer amphetamines to increase their ability to work, and after a number of months, the drug fries their brains.

No one on the station seems to care that these deaths are happening, and that sticks in O’Neil’s craw like nothing else. He begins investigating, and discovers in short order that the drugs are being brought in by Sheppard. Now O’Neil has to prove it, so he can bust the station manager and redeem a career that had been mired in the mud. There is some back and forth between O’Neil and Sheppard, but in the end O’Neil turns out to be totally intractable, so Sheppard calls in a pair of hired guns to kill the marshal, setting up a final act where O’Neil is forced to fight alone against the assassins while the rest of the residents on the station make themselves scarce and wait for it all to be over. From their perspective, with any luck, O’Neil will be taken care of quickly, and they can go back to shooting drugs, digging up titanium, and collecting bonus checks.

The final act is a great payoff. From the moment O’Neil discovers the miners are all high as Georgia pines the plot was building to some sort of final confrontation. The setting makes it even better. There isn’t much in the way of surprises in this film, but it never gets bogged down in its slow spots (i.e., any scene where O’Neil has to deal with his crumbling home life).

Sean Connery did well in his role, but it did have one gigantic flaw. One of the reasons O’Neil was sent to Io, apparently, is that he’s a shitty cop. It was understood that the drugs could flow freely because the new marshal wouldn’t be able to muster the competence to do anything about it. By O’Neil’s own admission he’s a worthless officer of the law. And yet, despite all these pronunciations, from multiple characters throughout the film, O’Neil is never, not once, the bumbling, useless police officer everyone insists he is. From day one he’s shown to be a ball buster who gets things done. It’s the complete opposite of what the script called for. Nevertheless, it doesn’t damage the film. Just what we see on screen and what we hear the characters say often doesn’t match.

Peter Boyle is good as the corrupt station manager, but he was never not good. A pleasant surprise comes from James B. Sikking as Sgt. Montone, O’Neil’s second in command. He’s a veteran on the station, with the thousand-yard stare to go with it. The only other production of note I can remember him from is his long run on Hill Street Blues. He was the comic relief in that drama, but in Outland he shows that he can play world-weary. Of final note is Frances Sternhagen as a crusty physician with a horrible attitude. She plays the equivalent of a western film’s sassy saloon owner who used to be a prostitute. She’s there to offer witticisms and play an ethical counterweight to O’Neil. She does fine, but there’s hardly a scene she’s in where her character isn’t being unpleasant.

Hyams crafted a hybrid film with Outland. It takes place far from Earth, but the setting is secondary to the story. It could have been set in a mining town in Ecuador, and the story would still work. As indicated above, it has elements of American westerns and crime thrillers. With a little more intent on the part of Hyams, it could have been a neo-noir film, as well. Hyams got the grit right, which was common in sci-fi films of the time (see George Lucas and Ridley Scott). As it is, the amalgamation of genres works very well. Outland is not just a good sci-fi film. It’s a good film in general.