Is it okay to watch a Mel Gibson film again? Has he paid enough Hollywood penance for being a drunken, anti-Semitic, Catholic fundamentalist? Because, let’s not forget, the man is an Oscar-winning filmmaker. Gibson’s personal travails matter little to this reviewer. If the idea of watching a film helmed by Mel Gibson still leaves a viewer with a bad taste in their mouth, even though Gibson spent the better part of a decade in the weeds, then just don’t watch it.

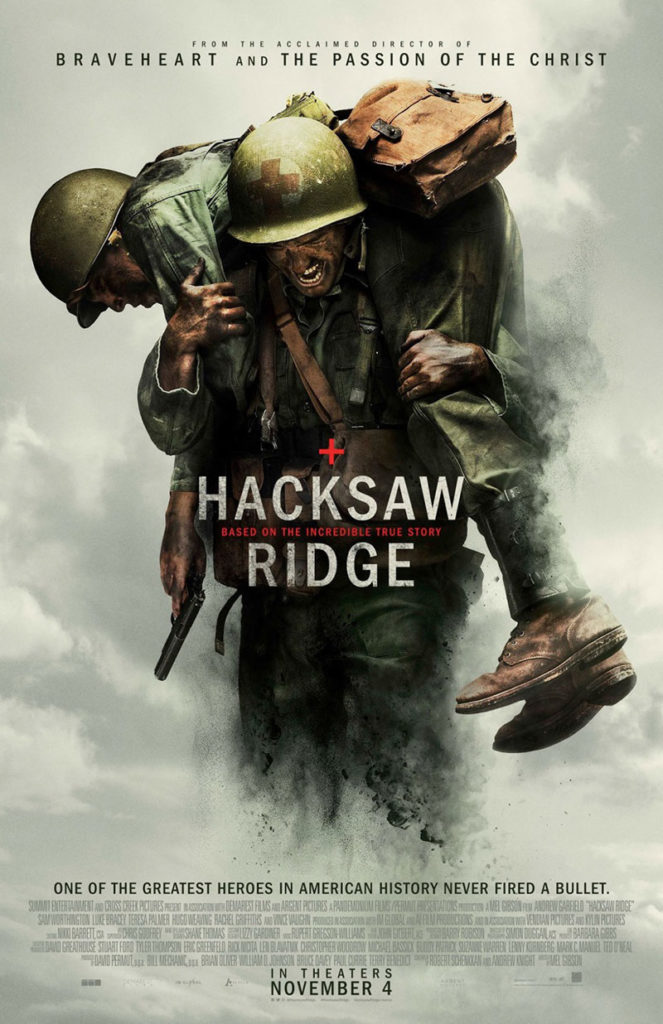

From last year, Hacksaw Ridge is Gibson’s first foray back in the director’s chair since 2006’s Apocalypto. Like in that film, Gibson doesn’t stray from behind the camera.

Andrew Garfield stars as Desmond Doss, a real-life winner of the Medal of Honor. The film traces elements of Doss’s time before the outbreak of World War 2, but the meat of the film is Doss’s service in the army during wartime.

Doss, for religious and personal reasons, refuses to commit violence of any kind, even going so far as to refuse to touch or shoot a rifle in training, when all one is shooting at is an inanimate target. He is as patriotic as any young American male of the day and it pains him to see his countrymen go off to war while he has the opportunity, because of his job, to stay home. Doss joins the army not to fight, but to become a frontline medic, sharing all the same dangers as infantry riflemen, but hopefully saving lives instead of taking them. It’s a laudable goal, but just about all of Doss’s brothers in arms hate his guts, mistaking his pacifism for cowardice.

This did happen to Doss in real life, but Gibson put about as much sophistication into this act as one would expect from one of Ron Howard’s squishier films. There’s not a lot happening here other than people being jerks to a man who refuses to compromise his religious beliefs. Hmm. Perhaps Gibson still feels stung about  his stint as a persona non grata in Hollywood. Perhaps this film is as much about Gibson’s personal sense of persecution as it is about the exploits of a genuine war hero. Perhaps Gibson should have thought a little harder before piggybacking his own dramas onto those of someone who spent time in that most vile of human conditions — war.

his stint as a persona non grata in Hollywood. Perhaps this film is as much about Gibson’s personal sense of persecution as it is about the exploits of a genuine war hero. Perhaps Gibson should have thought a little harder before piggybacking his own dramas onto those of someone who spent time in that most vile of human conditions — war.

I liked this film, but in order to do so I had to put aside those moments in the film that were clearly about Gibson as much as Doss. This wasn’t helped by an ending where Doss is treated like a messiah. In that moment this film changes from a war movie into something more devotional, more hokey, and more tone-deaf. But I’m getting ahead of myself.

Back at the end of the second act, Doss wins the right to be a medic and never carry a gun. Right after, his unit is sent to fight on Okinawa, reinforcing US troops who are already there after the invasion of the island in 1945. Doss and the others in his company are green as hell, and completely unprepared for the experience of combat. This is a disingenuous scene. In real life, Doss had already seen combat throughout 1944, and had been decorated for his actions under fire. He was already proven brave and noble by the time he was sent to this new crucible. Shortening Doss’s story to Okinawa does a disservice to the facts in exchange for narrative expediency. But, it’s a movie, so this is hardly a crime against humanity.

Most of the film is generic claptrap. But Gibson’s wheelhouse has always been violence. Looking back through his filmography, starting with Braveheart, all of his directorial efforts since have been heavy on the blood. The combat scenes between the American soldiers and the Japanese are chaotic, nasty, and random. They aren’t as heavy on the realism as something like Saving Private Ryan or The Pacific. Rather, Gibson introduced some cartoonish feats of super-soldiery that has more in common with South Korean or Hong Kong cinema. The effect he was chasing was one of spectacle, rather than a grim portrayal of the realities of war.

Violence, I think, is important in a war film. Gibson may have been flashy with this combat, but it doesn’t commit the crime of omission that was standard in Hollywood fare of the past. War film violence isn’t like horror film violence. War films tell stories out of our history. The violence in these films carries with it a burden to educate. Maybe if more war films were dedicated to showing realistic violence the public would better understand what it means to send our military off on another adventure. Or maybe it would just anesthetize us.

Doss survives all the flying metal and limbs and saves life after life. According to a final tally Doss got 75 wounded soldiers to safety. He worked in an unimaginable hellscape and didn’t stop until he was wounded himself. He truly did go beyond the call of duty, and it is a joyful experience to see hope amid all this turmoil. And then in the end Gibson spoils it by turning Doss into an ersatz apostle. Oh, well.

What audiences get, then, is a movie in three parts. The first part, before any shots are fired in anger, is a Jimmy Stewart-esque American boy’s tale. The second part is a spectacular portrayal of war. The third and final part, mercifully lasting only minutes, is a redemption scene — an announcement of the blessed nature of Doss and Gibson, haloed in the glow of God’s light. The iconography is heavy in this part, but it’s still a decent flick.