Leave it to England, land of the most enthusiastic domestic gardeners in the world, to produce a monster flick about giant, carnivorous plants.

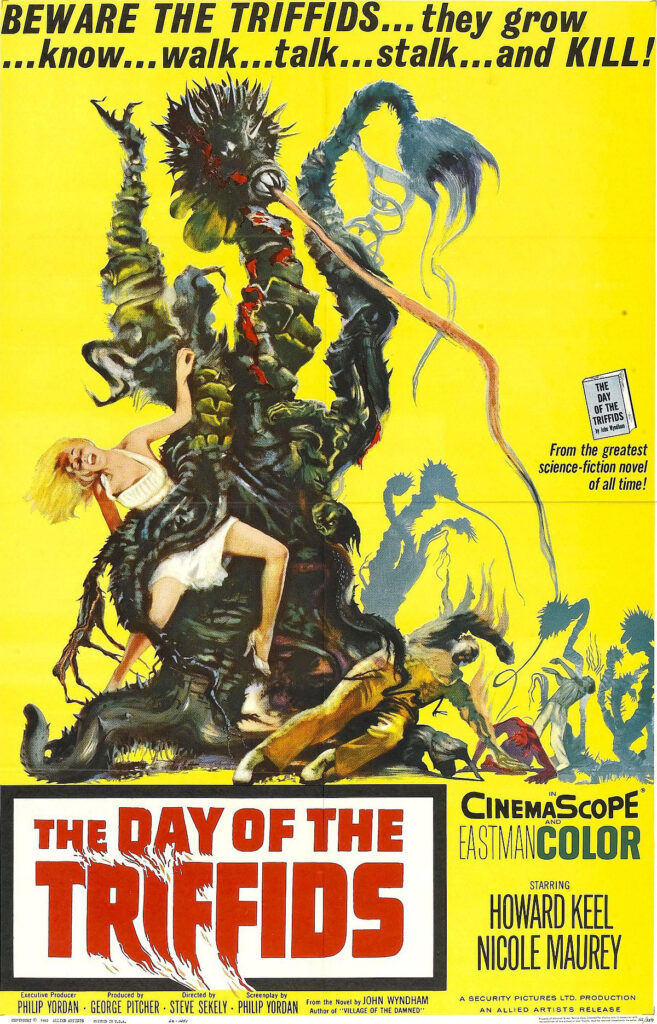

The Day of the Triffids comes to us from 1963. Adapted by screenwriter Bernard Gordon from the novel by John Wyndham, The Day of the Triffids tells the story of an alien invasion of Earth. But, these aren’t the normal, big-eyed, grey-skinned creatures with laser guns with which audiences are so familiar. These are, as noted above, huge, ambulatory plants that poison their victims and then consume them. They are creatures that require no sentience to carry out their invasion. Like the kudzu, they have strength in numbers.

The triffids arrived on Earth via spores released from the most spectacular meteor shower the world has ever known. They seed the ground, grow quickly, tear themselves loose from the soil, and go shuffling off to find food. So, how do these slow and stupid things pose an existential threat to civilization? After all, they’re just plants with a walking speed that’s more tortoise than hare. Well, Wyndham thought of that. The light show in the sky the night of the meteor shower was so  spectacular that the majority of humanity was outdoors taking it in…and the lights blinded anyone who saw them. Not so easy to get away from a hungry plant when one can’t see it coming.

spectacular that the majority of humanity was outdoors taking it in…and the lights blinded anyone who saw them. Not so easy to get away from a hungry plant when one can’t see it coming.

The hero of this film, Bill Masen (Howard Keel), first mate aboard a cargo ship, was one of the lucky few. He had eye surgery in London the week before the meteor shower, and was in the hospital, eyes covered and bandaged. The day after the shower, he rises to find the hospital deserted (a conceit later used by 28 Days Later and The Walking Dead). He peels off the bandages and leaves the hospital in search of answers.

Blind people wander the streets of London, but not so many to stretch the film’s budget. While on his way south to his vessel, Bill is joined by young Susan (Janina Faye), a doll-like runaway from a boarding school, who spent the previous night inside a windowless boxcar, thus saving her eyesight.

Meanwhile, a married pair of biologists, Drs. Tom and Karen Goodwin (Kieron Moore and Janette Scott), are stuck on an isolated rock offshore, carrying out field research based in an old lighthouse. It’s not marital bliss for these two. Tom is an alcoholic, and it was his bright idea for the couple to take leave from teaching university classes to do some real work in a place where it’s hard to get booze. It’s a desperation move, and is not paying off. But then, the triffids arrive, what little booze Tom has runs out, and, reinvigorated, he takes it upon himself to do a thorough investigation of the triffids, providing the audience with all the exposition they will want or need.

Bill and Susan set off on a journey that takes them from the south of England to a chateau in France, and a villa in Spain, searching for safe haven. But, the governments of Earth have collapsed. It’s just impossible to function when over 99% of the people on the planet have lost their sight.

Because this movie didn’t have a lot of cash with which to work, the expansive idea of civilizational collapse is explored only in passing. There are some early morning shots of Piccadilly devoid of people, and some matte work of a still and deserted Champs-Élysées, but that’s about it. The world appears more as it would if everyone disappeared rather than went blind. Audiences will just have to believe that everyone is choosing to sit in their homes and slowly starve to death rather than wander about.

The most harrowing scenes of the movie are interludes that don’t involve principal characters at all. Occasionally one of the protagonists will turn on a wireless radio, prolific items in this movie, and hear pleas for help from elsewhere. The perspective shifts to these endangered people. Viewers see a passenger jet, with the largest fuel tank known to man, in desperate search for a safe place to land. Everyone aboard, including the pilots, have been blinded. In another instance, an ocean liner is steaming ahead with no idea of its direction. Not a single person aboard can see. Apparently, even the fellas down in the boiler room took a little time off to watch the light show the night before. Anyway…

The film switches back and forth from set pieces featuring Masen doing battle with the occasional triffid, and more exposition from Forced Sobriety Island. Other names could be Save Our Marriage Island, or maybe A Psychological Experiment on the Effects of Paired Isolation Island. One gets the idea. These scenes are a bit of a chore.

The good news is, unlike many low-budget affairs from the UK, this film doesn’t wallow in long scenes of dialogue. That was a necessity in many films of the era, and on BBC television productions in particular, because they had even less dough to work with than poverty row studios in Hollywood. Director Steve Sekely, with an uncredited assist from UK horror stalwart Freddie Francis, kept the characters in constant danger, maintaining an even pace throughout the film. Sure, the characters don’t seem to be in as dire peril as in other creature features, but Sekely had to make plants dangerous. Plants. The degree of difficulty was high, and Sekely mostly pulled it off.

The budget really shows throughout the film, however. The special effects are low, low rent. In fact, they’re just plain bad. The burden of believability is placed squarely on the shoulders of the viewer. It’s not as if these effects were done without care. They are just cheap. The Polonia Brothers did better with their allowances back when they were teenagers.

That’s the harshest criticism I have for this movie, though. In the end, The Day of the Triffids is a decent example of b-monster horror from the 1950s and ’60s. This is about what one could expect of the era, kin to anything Roger Corman or Bert I. Gordon was making at the time. In the Watchability Index, The Day of the Triffids displaces Martial Law at #233.